Context: In August 2020, Epic Games sued Google (on the same day as they sued Apple) over monopoly abuse and other anticompetitive conduct in the Android app distribution business. The case went to trial in November 2023, and on December 11, 2023, a San Francisco jury found for Epic on all counts.

What’s new: On January 11, 2024, Judge James Donato of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California will see the parties again to discuss the next steps. This article discusses Google’s likely strategy to have the jury verdict thrown out in whole or in part (for which a December 1, 2023 Google filing provides an indication), or at least to ensure that the court won’t impose remedies that would have teeth.

Direct impact: Post-trial proceedings will still take some time, and just like in Epic Games v. Apple, an injunction ordered by the district court would probably not be enforceable during the appellate proceedings.

Wider ramifications: This case has the potential, provided that the jury verdict stands and that impactful remedies are ordered as well as ultimately enforced, to demonopolize the mobile app distribution landscape more than any other. It may encourage policy makers and regulators in various jurisdictions to take decisive action (also against Apple). Not only Epic Games stands to gain important freedoms, but also other potential app store operators such as Microsoft, the app economy, and ultimately consumers may benefit from greater choice, better information, more innovation and lower prices.

Epic Games scored an important trial victory over Google when a jury handed down a verdict on December 11, 2023 that answered each and every question in Epic’s favor. But Epic’s CEO Tim Sweeney, who personally attended almost the entire trial, knows that the jury verdict all by itself can’t open up the Android app distribution market. Five days after the verdict, the Financial Times published a paywalled interview with him in which he explained that there was risk of “fake” remedies, and said that it would take “a multipronged set of remedies” to demonopolize the Android app distribution market.

The January 11, 2024 hearing merely serves a case management purpose: Judge Donato will discuss with counsel how to structure the post-trial proceedings. There will foreseeably be a remedies hearing in the late winter or in the spring–followed by some kind of injunction–and an appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

This article will first discuss the question of remedies and then talk about an outline of arguments Google will likely raise on appeal based on the positions it has taken throughout the litigation, culminating in a filing Google’s lawyers made on December 1, 2023 (i.e., 10 days prior to the verdict).

games fray would like to credit The Verge for its detailed play-by-play trial coverage. Meanwhile, the public trial exhibits have been docketed, providing another important source of information.

Insufficient remedies could necessitate follow-on litigation

Epic’s founder has a reasonable apprehension with respect to remedies. There simply is precedent for Apple and Google imposing, as Mr. Sweeney now fears, an app tax of effectively the same amount (30%; there are exceptions, but they are not relevant in this case nor do they apply to a substantial percentage of mobile app revenues) wherever they have to accept alternative payment methods. The 30% tax–which is effectively even higher for various reasons such as the way they pass on parts of digital platform taxes and because of the way particularly Apple has made app promotion more expensive–is primarily a monopoly rent, but it also includes what payment processing costs even in a competitive market (a low single-digit percentage). So if there is a market in which credit card companies charge, for example, 3%, and Google still collects 27%, the total is the same.

That has happened already in different jurisdictions in Europe (a regulatory proceeding concerning iOS dating apps in the Netherlands) and Asia (South Korea, where the telecommunications law was amended with a reference to mobile app stores, and India, where the antitrust watchdog, the Competition Commission of India, investigated and ruled against Google). And Mr. Sweeney realistically expects that a pretrial settlement between Google and the attorneys-general of three dozen U.S. states and the District of Columbia may allow Google to do the same, which Google calls “User Choice Billing.” The term is misleading as users have always had the choice between paying with different credit cards, authorizing charges against their bank accounts or using services like Paypal. Developers, however, had no choice but to use Google’s (and Apple’s) in-app payment system that comes with the 30% tax and subjects them to all sorts of rules (app review guidelines) that are largely just designed to maximize revenues and control for Apple and Google, usually under such pretexts as privacy, security and quality.

The San Francisco jury held Google in violation of the antitrust laws, and it did so on various grounds. But the verdict itself does not specify what app tax would be reasonable and non-discriminatory, nor is Judge Donato likely to take a position on that.

Epic and Google will seek to convince Judge Donato of different approaches, with Google foreseeably arguing that User Choice Billing is sufficient (all the while stressing that the verdict should not stand) and Epic seeking something more impactful.

Before the case was even put before the jury, Google prevailed on summary judgment with respect to an important question: Judge Donato held that there was no antitrust duty to deal that would require Google to distribute alternative app stores (an app store also needs an app of its own as its front end) through Google Play. Epic could appeal that summary judgment, but the hurdle for a duty to deal is very high under U.S. antitrust law (Aspen Skiing and Trinko), requiring among other things that the monopolis abandoned a prior profitable deal.

A structural solution could nevertheless enable rival app stores (by Epic, Microsoft and others such as Amazon or Steam maker Valve) to compete on a reasonably level playing field with the Google Play Store, to the extent one can compete with someone who possesses the Power of Default. But Google might then seek to tax those rival app stores.

In general, there are two directions in which this can go in practical terms:

- If the remedies are (when all is said and done, i.e., when all appeals have been exhausted) very good, the Android app distribution market will be demonopolized in such a way that any attempts by Google to tilt the playing field through technical measures and/or unfair commercial rules could give rise to contempt-of-court sanctions.

- If the court does not go far beyond saying that what Google did in the past was unlawful, but lets Google implicitly or explicitly get away with what it calls User Choice Billing, Epic and/or other parties would have to bring another lawsuit seeking to reduce the app tax imposed by Google.

Theoretically there would also be a third way, but I have little hope that it would work: Google could actually view more openness as an opportunity to better compete with Apple. Google could have the developer community on its side, and a significant shift of market share from iOS to Android (in the U.S., the opposite has been occurring for years now) could result from developers encouraging and through lower prices and other benefits incentivizing migration from iOS to Android. But there are no signs of Google considering a new strategy a superior option over clinging to its “fauxpenness” (fake openness). It may just be too tempting to own, control and milk a walled garden.

Glimpse into Google’s appellate strategy

Judge Donato gave Google a strict limit of two pages to summarize in an almost telegraphic style its arguments for a judgment as a matter of law (JMOL). The legal standard for a JMOL is that no reasonable jury could ever decide–or, after the fact, could have decided–otherwise. That is a relatively but not insurmountably high standard, reflective of the important constitutional role that U.S. juries play. If the same factual findings as in the December 11 verdict had been made by Judge Donato himself, they would enjoy much less deference from the appeals court.

JMOL is not the only basis for an appeal. Google could also dispute the fairness of the jury instructions (which would, however, merely result in a retrial if successful). It is likely, however, that Google’s lawyers will either focus exclusively on JMOL or clearly prioritize that approach on appeal. Additionally to disputing the underlying merits, Google can argue that remedies are overreaching, but for now we don’t know what kind of injunction Judge Donato will order. Chances are that no matter what he decides, Google will say it goes too far.

To keep things simple, let us not distinguish here between whether a given Google argument means that a certain question should already have been resolved in its favor at the summary judgment stage (the way the duty-to-deal part was thrown out), i.e., ahead of trial, or whether JMOL was warranted after the presentation of evidence.

The facts are not really on Google’s side: based on what was reported and what the public trial exhibits suggest, Google was mostly just able to present facts that could serve to muddy the water or make the jury doubt Epic’s credibility, while Epic showed some real smoking guns. Therefore, Google’s arguments are, in the end, going to be more about the law than the facts. Put differently, its lawyers will have to say that despite the facts making Google look really bad, some selective facts are sufficient to decide the case for Google just because U.S. antitrust law sets a high bar for the kinds of claims that Epic is pursuing.

The December 1 list of JMOL arguments (PDF) is going to be the pool from which Google’s lawyers will select most if not all of their appellate arguments:

- Pointing to the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Epic Games v. Apple, which was favorable to Apple on Epic’s federal antitrust claims including a tying claim, Google says Epic’s per se tying claim fails. In other words, Google must at least have the chance to justify tying (here, the fact that app developers must accept Google’s in-app payment terms in order for their apps to be eligible for distribution through the super-dominant Google Play app store). However, Judge Donato explained to the jury that identifying a tie was not the end of the analysis, and that the equivalent of a rule-of-reason analysis (i.e., analyzing potential justifications) was needed in the tying context. Therefore, this first item alone would just be an interim step, but insufficient for Google to prevail on.

- Epic originally pursued a per se theory (again, this means that no justification can even be attempted) for all of Google’s “Project Hug” (later renamed “Games Velocity Program”) agreements with about a dozen game makers. Toward the end of the trial, Epic’s counsel narrowed that position and focused only on the agreement with Activision Blizzard King (ABK), saying that at least with respect to ABK the court should recognize Epic had a strong argument of an anticompetitive dealing constituting a per se violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act. Judge Donato disagreed with Epic, and the jury nevertheless found those dealings between Google and game makers (one of which is ABK) anticompetitive. This, too, is an item that wouldn’t be sufficient for Google to prevail on, as the jury found against it regardless.

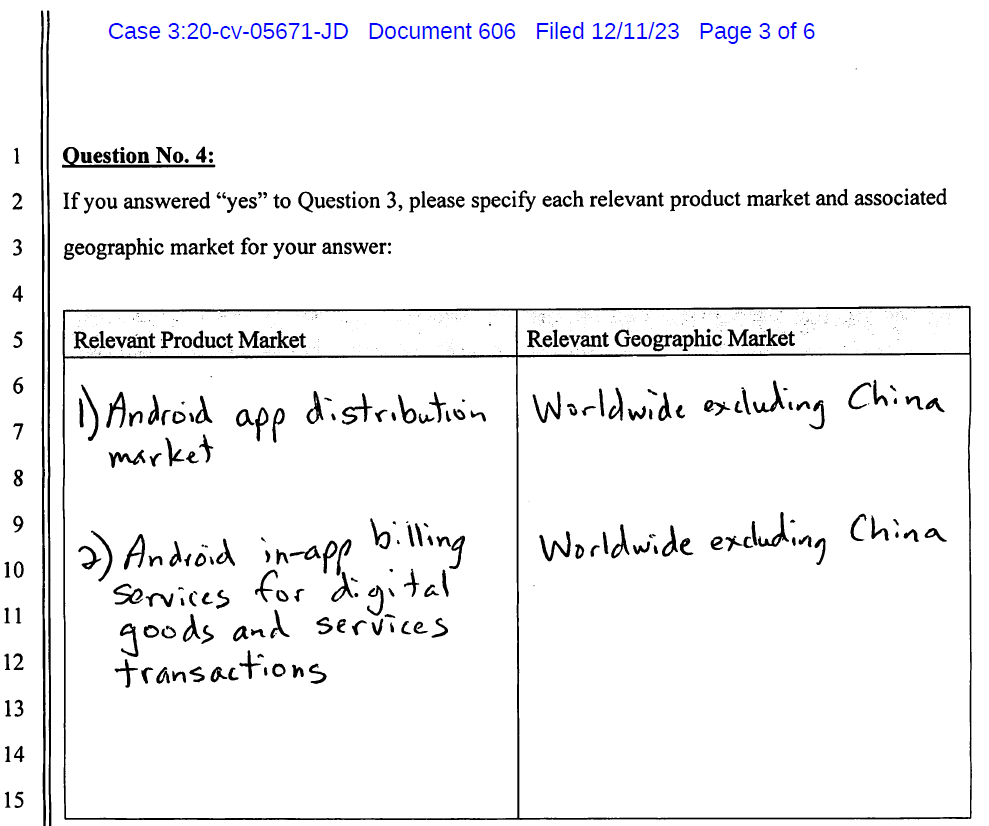

- The jury adopted exactly the market definitions that Epic espoused and Google disputed. Google’s argument is that (i) “Epic has not offered legally sufficient evidence to limit the products markets to services for the single brand of ‘Android’ devices,” (ii) “Epic is collaterally estopped from asserting that Apple and Google to not compete with respect to app distribution” (because of what Epic said in the Apple litigation), (iii) “Epic failed to present sufficient evidence that out-of-app payment systems [such as people making payments on game makers’ websites] are not reasonable substitutes for the in-app payment systems” and (iv) Google disputes that Epic has sufficient effidence for a worldwide market excluding China (Google would like the market to be just the U.S., where Android’s market share is substantially below the global share and where Google is losing ground to Apple on a daily basis; and even if it was an international market, China should be included, though the regulatory enviroment there is unique).

Judge Donato did not buy any of those arguments during the trial and is highly unlikely to agree now. While none of Google’s arguments is particularly compelling, it is highly likely that market definition will be put front and center in Google’s appeal. - Google then makes the argument that it lacks monopoly or market power “in any legally supported market.” That argument depends on market definition (previous item). Google’s other argument here is that there is no evidence of its prices being “above a competitive level for the actual services it provides” or being “not competitive with alternative platforms.” In that regard, Google will point to Apple’s terms, but the “Goopple” duopoly simply has very similar terms and Apple even tried to support Google through its trial testimony. Google will likely point to the commissions charged by video game console makers, but that is a rather different business model. The last part of Google’s “no monopoly power” argument is that it already imposed the 30% rate at the very beginning, when it technically couldn’t have market power. That is an argument Apple also made against Epic. Google made that argument to the jury, and the jury nevertheless found against Google, but this may very well come up again on appeal.

- No anticompetitive effects: provided that Epic has no per se claims (and Judge Donato didn’t instruct the jury to apply a per se standard to anything at any rate), Google says there is no claim where Epic can prevail on the basis of the rule of reason “because no reasonable jury could conclude that the conduct challenged is anticompetitive or harmed competition.” Google preserves a laundry list of arguments, most of which come down to saying that Epic failed to present evidence for essential elements of a rule-of-reason claim. It remains to be seen which of these arguments Google will prioritize on appeal, but some rule-of-reason argument appears very likely to be made.

- U.S. antitrust plaintiffs must show at a certain stage of the analysis (which is not always reached) that the defendant would have had a less restrictive alternative. Google claims that the evidence presented by Epic and its expert’s testimony support Google’s security arguments and make that one non-pretextual.

- With respect to tying again, Google says Epic could not show that Google Play (the app store) and Google Play Billing (the in-app payment system that also collects the 30% tax) “are separate products.” This was also an argument Apple made with respect to iOS and Apple’s IAP system in its litigation with Epic.

- Finally, Google notes that legal insufficiencies cannot be overcome by the adverse inference instruction by which Judge Donato told the jury it may assume Google’s systematical deletion of sensitive chats (over which he will launch an investigation of Google’s conduct separate from this case, as he views it as an assault on the U.S. litigation system) has resulted in important evidence being withheld from the jury. It is common sense that this must be the case.

What Google means now when it says that “[a]n adverse inference instruction cannot salvage claims that are legally insufficient” is that even if the adverse inference instruction stands (because Google may not appeal it, as it will have to prioritize its arguments, or because the related part of the appeal may fail), Google’s arguments that Epic failed to present evidence that can legally support its antitrust claims must be evaluated based on the evidence that was actually presented. In other words, the court (or an appeals court) should not assume that the unlawfully-deleted chats would have contained just the pieces that Google says were missing to support certain claims and theories.

The objective of this second part of the present article was just to provide an overview of arguments most likely to be advanced by Google not only in the months but even the years ahead. This will go on for quite some time if the parties don’t settle. Epic is a very principled litigant. One doesn’t have to agree with everything they ever said or did, but so far they have definitely not been receptive to fake solutions, unlike all of their temporary co-plaintiffs. It is a safe assumption that Epic will fight for remedies and, if necessary, even bring follow-on litigation. Google also appears determined to exhaust all appeals if need be.

games fray will follow major app store cases as well as app distribution-related regulatory and legislative proceedings involving not only Google but also Apple (whose rules are even more restrictive than Google’s, but it is harder for courts and juries to identify inconsistencies than in Google’s dealings).